“Take shorter showers! Recycle! Turn off your lights!” We’ve been hearing about the power of individual environmental actions for years—and as a tree-hugging, Prius-driving vegetarian myself, I certainly do my best to live by them. However, today's most pressing environmental challenges–climate change, plastic pollution, sea level rise–are so enormous that they can’t be solved on the individual level alone. People must work together, becoming greater than the sum of their parts, to affect issues on this scale.

That’s where collective action comes in. Collective action happens when multiple people come together to push for change–rallying for new environmentally friendly policies, for example, or attending community litter cleanups. And it can be especially powerful when spurred by young people, who, research shows, have a strong influence on the adults in their lives and who will soon become adults themselves.

Unfortunately, we don’t really know what drives young people to take collective action for the environment, which makes it hard to know how to encourage more of this action.

My dissertation research in Dr. Kathryn Stevenson's Environmental Education Lab at North Carolina State University worked to address this. I looked at whether we can predict a young person’s engagement in collective environmental actions the same way we’ve historically predicted engagement in individual actions.

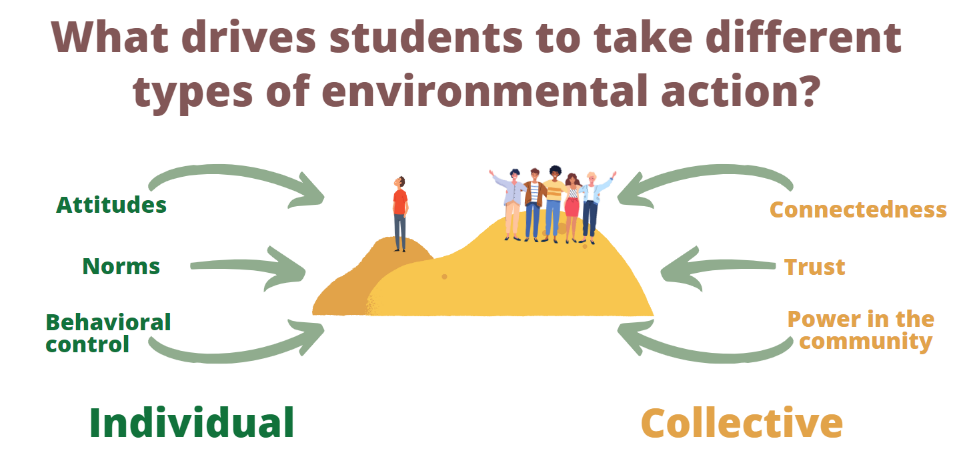

Let’s break that down a little more: We social scientists often try to predict behavior with three factors: a person’s attitudes, what the people around them think (norms), and how easy they think the behavior is to take (behavioral control).

From the fall of 2020 to the spring of 2022, I surveyed hundreds of North Carolina high school students about the types of environmental actions they take–both individual and collective–as well as different factors that might drive these behaviors.

What I found is that, while our “usual suspects” of attitudes, norms, and behavioral control are pretty good at predicting individual environmental behavior, they’re pretty bad at predicting collective behaviors. In other words, our usual way of predicting behavior just doesn’t work at the collective scale.

Instead, collective behaviors are better predicted by things like how many people the student talks to about environmental issues, how much power they feel they have in their community, and how much they trust other members of their community. I also found that students who were less hopeful about their personal ability to make a difference for the environment were more likely to join in collective efforts–perhaps seeing themselves as insufficient alone, but powerful together.

Looking at these drivers–connectedness, trust, power–it’s clear that efforts to foster collective action for the environment need to look different than efforts to foster individual action. To move towards collective action, we need to start intentionally bringing people together in conversation and collaboration. Then, we can truly work towards solutions that are powerful enough to meet the pressing needs of our planet today.

That’s where collective action comes in. Collective action happens when multiple people come together to push for change–rallying for new environmentally friendly policies, for example, or attending community litter cleanups. And it can be especially powerful when spurred by young people, who, research shows, have a strong influence on the adults in their lives and who will soon become adults themselves.

Unfortunately, we don’t really know what drives young people to take collective action for the environment, which makes it hard to know how to encourage more of this action.

My dissertation research in Dr. Kathryn Stevenson's Environmental Education Lab at North Carolina State University worked to address this. I looked at whether we can predict a young person’s engagement in collective environmental actions the same way we’ve historically predicted engagement in individual actions.

Let’s break that down a little more: We social scientists often try to predict behavior with three factors: a person’s attitudes, what the people around them think (norms), and how easy they think the behavior is to take (behavioral control).

From the fall of 2020 to the spring of 2022, I surveyed hundreds of North Carolina high school students about the types of environmental actions they take–both individual and collective–as well as different factors that might drive these behaviors.

What I found is that, while our “usual suspects” of attitudes, norms, and behavioral control are pretty good at predicting individual environmental behavior, they’re pretty bad at predicting collective behaviors. In other words, our usual way of predicting behavior just doesn’t work at the collective scale.

Instead, collective behaviors are better predicted by things like how many people the student talks to about environmental issues, how much power they feel they have in their community, and how much they trust other members of their community. I also found that students who were less hopeful about their personal ability to make a difference for the environment were more likely to join in collective efforts–perhaps seeing themselves as insufficient alone, but powerful together.

Looking at these drivers–connectedness, trust, power–it’s clear that efforts to foster collective action for the environment need to look different than efforts to foster individual action. To move towards collective action, we need to start intentionally bringing people together in conversation and collaboration. Then, we can truly work towards solutions that are powerful enough to meet the pressing needs of our planet today.